What is Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia?

Pulseless ventricular tachycardia, often abbreviated as pVT, represents a grave medical emergency that demands immediate and decisive intervention. It is a life-threatening cardiac arrhythmia characterized by a rapid, abnormal electrical activity in the ventricles of the heart that, despite its organized appearance on an electrocardiogram, fails to produce an effective heartbeat or palpable pulse. This condition signifies a profound disconnect between the heart’s electrical impulses and its mechanical pumping function, leading to a complete cessation of blood flow to the body’s vital organs. The immediate recognition and aggressive treatment of pVT are paramount, as it is a direct precursor to sudden cardiac arrest and, if left unaddressed, will inevitably result in sudden cardiac death. For healthcare providers, comprehensive training in the identification and management of pVT is not merely beneficial but absolutely critical to improving patient outcomes and saving lives. The ability to promptly identify this condition and initiate life-saving measures is a cornerstone of emergency cardiac care.

Understanding Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia

The fundamental difference between pulseless ventricular tachycardia and regular ventricular tachycardia lies in the heart’s ability to generate an effective mechanical contraction.

Pathophysiology

In typical ventricular tachycardia, the heart beats rapidly, but it still maintains some degree of pumping efficiency, often resulting in a palpable pulse and blood pressure, albeit possibly compromised. However, in pVT, the electrical impulses, while appearing organized on a cardiac monitor with wide QRS complexes, are too rapid and disorganized to allow the ventricles to fill adequately and pump blood effectively. This leads to a complete loss of effective mechanical function, meaning the heart is electrically active but mechanically inert, resulting in no discernible pulse or blood pressure. This severe electrical-mechanical dissociation underscores the critical nature of pVT and why it requires immediate and aggressive intervention. The heart’s inability to pump blood effectively means that vital organs, particularly the brain, are rapidly deprived of oxygen, leading to rapid deterioration and, if untreated, irreversible damage and death.

Risk Factors

Several factors can increase an individual’s risk of developing pulseless ventricular tachycardia. Underlying cardiac conditions are a primary contributor, including previous myocardial infarction or heart attack, congestive heart failure, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. These conditions can create structural abnormalities or electrical pathways within the heart that predispose it to re-entrant circuits, leading to sustained ventricular arrhythmias. Electrolyte imbalances, such as severe hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia, can significantly alter the heart’s electrical stability, making it more susceptible to developing pVT. Certain medications can also induce or exacerbate ventricular arrhythmias. For instance, some antiarrhythmic drugs, while intended to correct abnormal rhythms, can paradoxically create new ones under specific circumstances. Structural heart diseases, whether congenital or acquired, can also increase the risk by creating areas of scar tissue or abnormal muscle that disrupt normal electrical conduction. Understanding these risk factors is crucial for prevention and for identifying individuals who may be at higher risk for experiencing this life-threatening event.

Recognition and Assessment

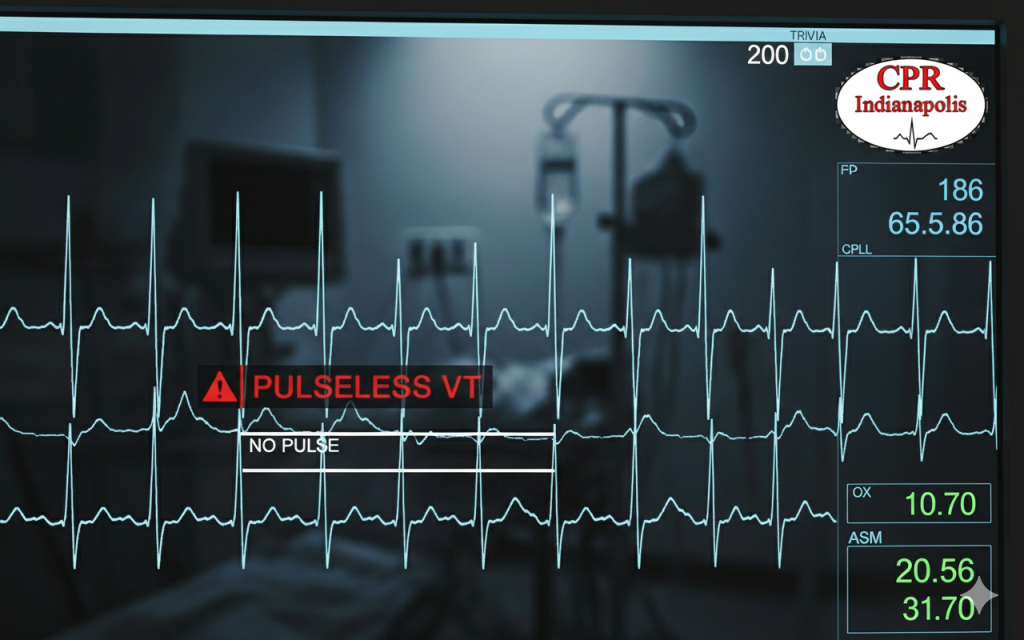

Recognizing pulseless ventricular tachycardia requires a swift and accurate assessment of the patient’s clinical presentation and a careful interpretation of their electrocardiogram.

Clinical Presentation

The hallmark clinical sign of pVT is the absence of a palpable pulse, despite the presence of an organized rhythm displayed on the cardiac monitor. This distinction is vital; it’s not enough to simply see ventricular tachycardia on a screen; a pulse check is essential. Patients will typically experience an abrupt loss of consciousness as blood flow to the brain ceases. This will be accompanied by an absence of blood pressure and may also manifest as cyanosis, a bluish discoloration of the skin due to lack of oxygen, and signs of severe respiratory distress. On the electrocardiogram, pVT is characterized by wide QRS complexes, typically measuring greater than 120 milliseconds. The heart rate is usually very rapid, ranging from 150 to 250 beats per minute, and the rhythm can be regular or slightly irregular. Distinguishing pVT from other arrhythmias, such as supraventricular tachycardia with aberrancy, is critical and relies on a comprehensive understanding of ECG characteristics and clinical context.

Call Us Now

Get the Best CPR Class in Indianapolis Today!

Immediate Management Protocol

Primary Assessment (CAB Approach)

The immediate management protocol for pulseless ventricular tachycardia follows the basic principles of advanced cardiac life support, beginning with a primary assessment using the Circulation, Airway, Breathing or CAB approach.

The very first step is to check for a pulse. If no pulse is present, immediate action is required. Simultaneously, attention should be given to airway management, ensuring patency to facilitate oxygen delivery, and breathing support, which involves providing rescue breaths or mechanical ventilation. Once the absence of a pulse is confirmed, high-quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation or CPR must be initiated without delay.

High-Quality CPR

High-quality CPR is characterized by specific parameters: compressions should be delivered at a depth of at least two inches for adults, at a rate of 100 to 120 compressions per minute. It is crucial to minimize interruptions in chest compressions, as this directly impacts the effectiveness of blood flow to vital organs. Proper hand placement, typically on the lower half of the sternum, is essential for effective compression, and team coordination during resuscitation efforts ensures a synchronized and efficient response.

Advanced Life Support Management

Defibrillation

Advanced life support management for pVT centers on immediate defibrillation, pharmacological interventions, and advanced airway management. Defibrillation is the cornerstone of treatment for pVT and should be delivered as the first-line therapy as soon as a defibrillator becomes available. The rapid delivery of an electrical shock can reset the heart’s electrical activity and restore a normal rhythm. The energy levels for defibrillation vary depending on whether a biphasic or monophasic defibrillator is used, with biphasic defibrillators typically requiring lower energy settings. Safe defibrillation techniques, including ensuring a clear area and shouting “clear,” are paramount to protect both the rescuer and the patient. Following each shock, a post-shock pulse check is necessary to assess for the return of spontaneous circulation.

Pharmacological Interventions

Pharmacological interventions play a supportive role. Epinephrine administration is a critical component of resuscitation, given to enhance myocardial contractility and peripheral vasoconstriction, thus improving blood flow during CPR. For cases that are refractory to initial defibrillation and epinephrine, antiarrhythmic medications like amiodarone or lidocaine may be administered. Magnesium is specifically indicated for suspected torsades de pointes, a polymorphic form of ventricular tachycardia. Proper medication dosing and routes of administration, typically intravenous or intraosseous, are essential.

Airway Management

Lastly, advanced airway placement considerations, such as endotracheal intubation, should be made to secure the airway and ensure adequate ventilation. Ventilation strategies during CPR should focus on avoiding hyperventilation, which can paradoxically decrease venous return and compromise coronary perfusion.

Special Considerations

Reversible Causes (H’s and T’s)

Special considerations in the management of pulseless ventricular tachycardia include identifying and addressing reversible causes, often referred to as the “H’s and T’s,” and managing refractory cases. The H’s and T’s mnemonic helps healthcare providers remember potential underlying issues that can be corrected to improve outcomes. These include hypovolemia, hypoxia, hydrogen ions or acidosis, hypo or hyperkalemia, and hypothermia. The Ts represent toxins, tamponade, tension pneumothorax, and thrombosis, both coronary and pulmonary. Identifying and treating these underlying conditions can significantly improve the chances of successful resuscitation.

Refractory Cases

For cases that are refractory to standard treatment, meaning they do not respond to initial defibrillation and pharmacological interventions, alternative strategies may be considered. These can include double sequential defibrillation, where two defibrillators are used to deliver shocks in rapid succession, or alternative antiarrhythmic medications. Mechanical CPR devices can provide consistent and effective chest compressions, particularly during prolonged resuscitation efforts or patient transport. In highly specialized settings, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or ECMO may be considered, which involves circulating the patient’s blood outside the body to provide oxygen and remove carbon dioxide, effectively bypassing the heart and lungs to allow for recovery.

Post-Resuscitation Care

Return of Spontaneous Circulation (ROSC)

After the return of spontaneous circulation, or ROSC, robust post-resuscitation care is vital for optimizing patient outcomes and minimizing neurological damage. Immediate post-cardiac arrest care focuses on stabilizing the patient’s hemodynamics, which includes meticulous monitoring of blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen saturation. Neurological assessment is crucial to evaluate the extent of brain injury and guide further interventions.

Targeted Temperature Management

Targeted temperature management, or TTM, is a critical component of post-resuscitation care for comatose patients after cardiac arrest. The indications for TTM typically include adults who remain comatose after ROSC following cardiac arrest of presumed cardiac origin. The implementation protocols involve inducing and maintaining mild hypothermia for a specific duration, followed by controlled rewarming. Monitoring during therapy includes continuous core temperature measurement and careful assessment for complications. The goal of TTM is to improve neurological outcomes by reducing cerebral metabolic rate and preventing secondary brain injury.

Prevention and Education

Preventing pulseless ventricular tachycardia and improving community-wide cardiac arrest survival involves a multifaceted approach encompassing risk factor modification and public education.

Risk Factor Modification

Risk factor modification includes promoting healthy lifestyle changes, such as maintaining a balanced diet, engaging in regular physical activity, and avoiding smoking, all of which can reduce the risk of underlying cardiac conditions. Medication compliance for individuals with pre-existing heart conditions is also paramount to prevent arrhythmias. Regular cardiac monitoring for high-risk patients, such as those with certain inherited heart conditions or a history of arrhythmias, can help identify and manage issues before they escalate to pVT.

Public Education

Public education plays a critical role in empowering the community to respond effectively to cardiac emergencies. This includes emphasizing the importance of bystander CPR, as early CPR significantly increases survival rates. Promoting automatic external defibrillator or AED use in the community, through widespread placement and training, allows immediate defibrillation before emergency medical services arrive. Education on the recognition of cardiac emergency symptoms enables individuals to call for help promptly, leading to earlier intervention.

Training and Certification Requirements

Training and certification requirements for healthcare providers are fundamental to ensuring a competent and coordinated response to pulseless ventricular tachycardia. Basic Life Support, or BLS, certification is the foundational requirement for all healthcare providers, ensuring they possess the essential skills for immediate life support.

4 FAQs About Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia

- What is pulseless ventricular tachycardia? Pulseless ventricular tachycardia (pVT) is a life-threatening heart rhythm where the heart beats extremely fast but cannot pump blood effectively, resulting in no detectable pulse. It requires immediate CPR and defibrillation.

- How do you recognize pulseless ventricular tachycardia? Patients with pVT will be unresponsive and have no pulse, despite showing a rapid, wide-complex rhythm on the cardiac monitor. The person may appear to be in cardiac arrest with no signs of circulation.

- What is the emergency treatment for pulseless VT? Treatment follows the cardiac arrest algorithm: immediate high-quality CPR, rapid defibrillation, advanced airway management, and medications like epinephrine and amiodarone as part of ACLS protocols.

- Can pulseless ventricular tachycardia be prevented? While not always preventable, risk can be reduced by managing underlying heart conditions, avoiding triggers like certain medications or electrolyte imbalances, and ensuring proper cardiac care for at-risk patients.

Call to Action

Ready to save lives? Get certified in ACLS and BLS with CPR Indianapolis! Our American Heart Association courses provide the critical skills you need to recognize and treat pulseless ventricular tachycardia. Join our stress-free, hands-on classes today and become confident in emergency cardiac care. Enroll now at CPR Indianapolis – Indianapolis’ best CPR training site.